Mississippi goddamn

How an icon of the civil rights movement and her music inspire me today

The Work

In my twenties and thirties, I was very active in the international community of Reevaluation Counseling or Co-Counseling or RC. I spent up to ten hours a week going to classes and support groups, and at least four weekend workshops a year. I also taught classes and lead support groups. One focused area of RC which drew both me and my wife Kerrie was the work on racism. Within RC was born a movement called United to End Racism or UER. Here is a link to an RC website highlighting some of the events and publications on the topic.

There were many reasons that “the work” of ending racism was deeply meaningful to me at that time in my life. For starters, I entered elementary school in the affluent suburb of West Hartford, CT in 1973, at a time when court-ordered bussing was being implemented. Poor white, black and brown kids from inner-city Hartford were being bussed to my school, and it was a hot mess. No adult explained what was going on, but there were teachers who were seething, and if was very confusing for a kid. Just a few examples:

I was a blond haired, blue-eyed white kid, small for my size, with a mouth to defend myself. One day on the playground, one of the black boys from Hartford decided he was going to kick my ass, and began chasing me around the playground. Some brilliant inspiration saved me, and as I was running for my life, I yelled over my shoulder to him, “Hey, why do you want to beat me up? My dad is Black.” The way he skidded to a halt was both a tremendous relief and comical. Kind of like how you stop suddenly when you realize that you just stepped into the path of a skunk and really, really, really don’t want to get sprayed. He looked stunned, and just walked away, literally scratching his head. Lesson learned for me? This was totally about race.

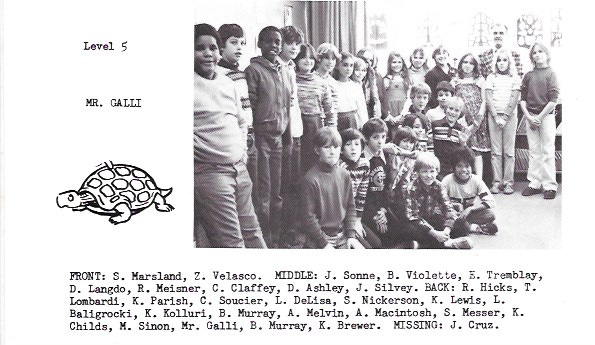

Mr Galli was my fifth and sixth grade teacher. He scared the bejesus out of us boys, because he would firmly massage our shoulders when he was upset with us, which triggered our burgeoning homo-erotic fears of our own feelings about other boys and men, and carried a not-so-subtle menace from his powerful hands. He was a short and stout man, with enormous bushy eyebrows and a facial expression of chronic irritation. Whatever the male version is of “chronic bitch face”, that’s what he had.

One day, two Hartford kids named Kenny Parish (Black) and Carl (white) had been pushing Mr Galli all day, and he was fed up. It was the end of the school day, and all the other kids had left the classroom, putting their chairs up on their desks and exiting to walk (because we could still walk home those days) or catch the bus. Kenny, Carl, and I were coming up the rear, and Mr Galli closed the door. He turned to look at Kenny and I was like “Uh-oh!” He grabbed Kenny by sides of his upper arms and lifted him two feet off the ground against the wall. I have zero memory of what was said, because of the deafening alarm bells going off in my head. My eyes were glued to Kenny’s levitating feet. At some point it ended, Mr Galli opened the door, and we all left. Lessons, plural, learned for me? 1) This was totally about race. 2) I was so insignificant, and powerless, that Mr Galli didn’t even care that I witnessed what he did, and knew I wouldn’t say anything lest the same thing happen to me.

Mixed-race couples and coupling

i. Maura Sinon was a classmate who also lived through the bussing days of Webster Hill Elementary School in Mr Galli’s class. She was a bold little Jewish girl, and she knew who she wanted. The fact that his skin was as black as night, she was the quintessential suburban kid and he was an inner-city Romeo, all seemed to motivate her further. I saw her holding hands with Rodney, even kissing in the coat room. I was stunned by her audacity, which far exceeded my own reckless stunts of youth. Where are you today Maura?

ii. My dad’s second wife Irene was Mexican American. She was a beautiful, curvaceous and sharp-tongued woman. As a boy I understood his attraction, even as she made life sheer terror for me, my sister and brother. I had nightmares about Irene into my early twenties.

She was from Los Angeles, CA, and he lived in Glastonbury, CT. They worked for the same company and met at a trade show. I remember listening to him talk to her on the phone in his apartment, and knew that something was up. He reminded me of a teenager in love. If my dad had moved out to LA, learned Spanish, and, well, basically reinvented his life and career, it could have worked out. Instead, his urban, sassy, brown-skinned and sun-loving wife moved to uptight, locked down, WASPy and bitter cold New England. She was miserable, and she took the rest of us along for the ride.

iv. Given what I saw transpire with my dad and Irene, I maybe could have known better, but as in Eilen Jewell’s song Bang, Bang, Bang, Cupid doesn’t take aim, he actually carries a sawed off shotgun and just randomly goes, bang, bang, bang. Jen was my friend. She whistled like no other, had a wicked laugh, an Afro in the mid-1980s, which was the essence of anachronistic. She also had lovely, soft honey brown skin. Her single mother, who was white, had adopted her. I don’t remember there ever being a father in the picture.

Her mom had a copy of The Joy of Sex, which we would look at together; my idea or hers, not sure. Approaching the end of our senior year, virginity felt like an albatross around my neck, and without too much planning or discussion, we both lost it together. I still have the green and yellow bracelet she wove for me, to honor the corn field where we lay. We headed off to different schools for college, and fell out of touch. Decades later, I understand that her mature love interests shifted to women.

v. When I was in nursing school, I was scrambling to get a nursing assistant position at a city hospital, and couldn’t make it happen. I had to settle for a low-paid, hard scrabble position doing home care in far-flung and strung-out neighborhoods of Philadelphia. This was on weekends, and the two assignments I had were at opposite ends of the city, entailing an hour each way on buses and The El. My first patient was a formal funeral home director who had suffered a stroke. They lived up above the funeral home, and I would get there so early that it was still dark out, so, super creepy. His wife was in chronic pain, disabled in her own ways, and needed all the help she could get. He was a big man, at least six feet tall and weighing about 200 lbs. Getting him out of bed, bathed and dressed was a physical workout of precarity for me, even though I’m a wiry 120 lbs.

Both the funeral director, and my next patient were African-American, and lived in Black neighborhoods. I never had a lick of trouble with my first assignment, because I was in and out, too early in the morning for the troublemakers. If that didn’t work out, I hoped that my white sneakers, white scrubs, and bag with Episcopal Home Health Service would grant me a pass.

The second assignment always felt dicier. Philadelphia was entering the peak of its crack epidemic, and I had to pick which side of the street I walked on—the one with the hookers selling their wares, or the one with the crackheads stumbling along, or sitting with head on their knees up against a building. This second patient was 100 years old, demented, and bed bound. He had been a farmer, and still had the muscles and left-hook to show for it. My jaw still clicks from the punch to the face I took while trying to change his diaper one morning.

The stench from his urine-soaked bedsheets made my stomach do backflips. I had to shoo away the cockroaches from his bed, the floor under my feet, the bathroom. The stairs creaked under my feet, and given the degree of dilapidation around me, I genuinely feared that I might fall through. Lunch would arrive on a tray from his daughter-in-law as I was finishing up. It was typically corned beef hash from a can, with buttered toast, and a full glass of rye whiskey. I think the whiskey worked better than drugs to keep him mellow. I would emerge onto the front stoop in time to see the change of shift, prostitutes and drug users gone, people walking to church in their Sunday finest.

There came a Sunday which is etched into my brain, and which I am still trying to unpack thirty five years later. I stepped out of the house onto the sidewalk and heard a boy’s voice yell, “Yo white guy!” I turned to my right and half a block away, saw two little Black boys, who couldn’t have been older than eight years old. One of them held a very large revolver, and as I looked at the big hole in the end of the barrel, my inner voice told me that this was real. He fired off six shots in my direction, and then they ran down the block and into a house across the street.

I still can’t tell you if that gun was real or not. Sometimes when I remember this event, I think I remember seeing the gun kick with each shot, and heard projectiles whizzing past my head. This much I can tell you for sure. I am deeply appreciative that many urban gangsters have never taken a pistol safety or marksmanship class, and so have no idea how to properly hold a gun. This fact alone has saved a lot of lives, and possibly mine, because they can’t shoot straight.

What I did next was completely irrational, and I wish I hadn’t, but I did. Once I realized that I was in fact, alive, and hadn’t peed or crapped myself, I ran after them. I leapt up onto their porch and began pounding on the door, saying something along the lines of “Come out here you little hooligans!” That didn’t last too long. With no answer or sign of activity inside, I walked back to my second patient’s house, and rang the doorbell. The family was visibly upset by my story and called the police. It took a while for the police van to arrive, with two white Philadelphia police officers. They were smiling, laughing, and treated it all like a big joke, which was pretty discouraging.

On The El ride home, I thought that this was the end of my home nursing career. I was wrong. Just before I went to bed that night I got a call at home. I have no idea how they got my number. It was the daughter-in-law. She said, “Listen, we’re really sorry about what happened to you today, but we don’t know what we would do without your help. Please come back. That won’t happen again, I promise. We took care of it.” That got my attention. How does one “take care” of such a situation.

It turns out that on that block of a poor neighborhood of Philadelphia, there were six mixed race couples. The variety was like an ethnic Rubik’s cube. White and Black, latino and Black, Filipino and Black, Vietnamese and Black, white-Italian and Black, Chinese and Black. They weren’t going to brook that type of behavior. That evening, ten men from the block presented themselves to the door of the home of those two little boys, and invited themselves inside. They asserted that under no circumstances would such an event ever, ever, happen again in their neighborhood. Because why? Well, if it did, they would nail 2 x 4 across their doors, poor gasoline around the house, and burn the house down with everyone inside. Understood? Yes.

I have run through this in my head more times than I can count, and the stream of thoughts are still akimbo. As much as I was impressed by the neighborhood’s response, and reassured that I could safely return, which I did (and never had any issue), I was and am also troubled by the threat they made. The 1985 MOVE bombing in Philadelphia destroyed two city blocks, resulting in the loss of 61 homes and leaving about 250 people homeless. In a city where the first black mayor gave the order to drop an incendiary bomb on a house with black men, women and children inside, and destroyed a working class black neighborhood, threats to burn down your home with you in it had a whole ‘nother level of meaning.

vi. I’m putting this out of order, in part, because I don’t want to end on a sour note. Chris and Leslie Jones, and their four boys, were members of Schuykill Friends Meeting, where I began attending Quaker worship at the impressionable age of fourteen years. Chris was a soft-spoken professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, and white. Leslie was the soft-spoken, firmly guiding, deeply spiritual mother of not only her band of boys, but also our meeting itself. She would break into song during meeting when the spirit moved her. She was shorter, round, and a lighter-skinned Black woman.

I remember that after I had grown up and was living in Philadelphia in my early twenties, I caught a ride back to my Nana’s in the countryside with Chris and Leslie. On the way, we stopped in to offer well wishes to a recently married couple, old friends of theirs. They were in their forties, living in a tidy working class Philly neighborhood, and the thirty-odd people in the house were all Black. Being with Chris and Leslie, I was treated like family, and I realized that it was a moment of firsts. It was the first time I was in the minority, the first time I had been in the home of a Black family, and the first time that I felt seen, accepted, welcomed, and even cared about by that family. There was lot of living before then for me to stack that up against, but I’m grateful for that moment.

Martin and Malcom

I don’t know how much most other white people have read, thought, watched movies, counseled, and just tried to live in a way that counters racism. I really don’t. I can just say that I’ve tried to think about this for a long time, and don’t think I know much more than when I started. I sure have made a lot of mistakes, but I decided a long time ago that it’s better for me to try, and make mistakes, than to be tip-toe careful and remain a good white man in my head alone. This Substack is another risk in making mistakes, as I don’t want to hurt or offend any of my African American colleagues, patients or friends, but here I am, writing. Sometimes a story just has to be written.

One thing I think I know is that there are many, many good Black people. We have been friends, loved each other, sang together, worshipped together, grieved together, counseled together, worked together, broken bread together. They have saved me from trouble and myself on more than a few occasions. And just like any other group of people, there are some serious stinkers. I’ve been robbed by them, shot at by them, threatened by them, and in the midst of those experiences, didn’t have a very good opinion of them.

My experience has been that getting to know the person you were taught to objectify and generalize about makes it much harder to cling to prejudice. Alternately, I think it can leave you with what I call postjudice. E.g. I attended African American churches three times when we lived in Philadelphia, and each time I heard a minister railing about the sins of homosexuality and God’s judgement in the AIDS epidemic. I don’t need to do that again.

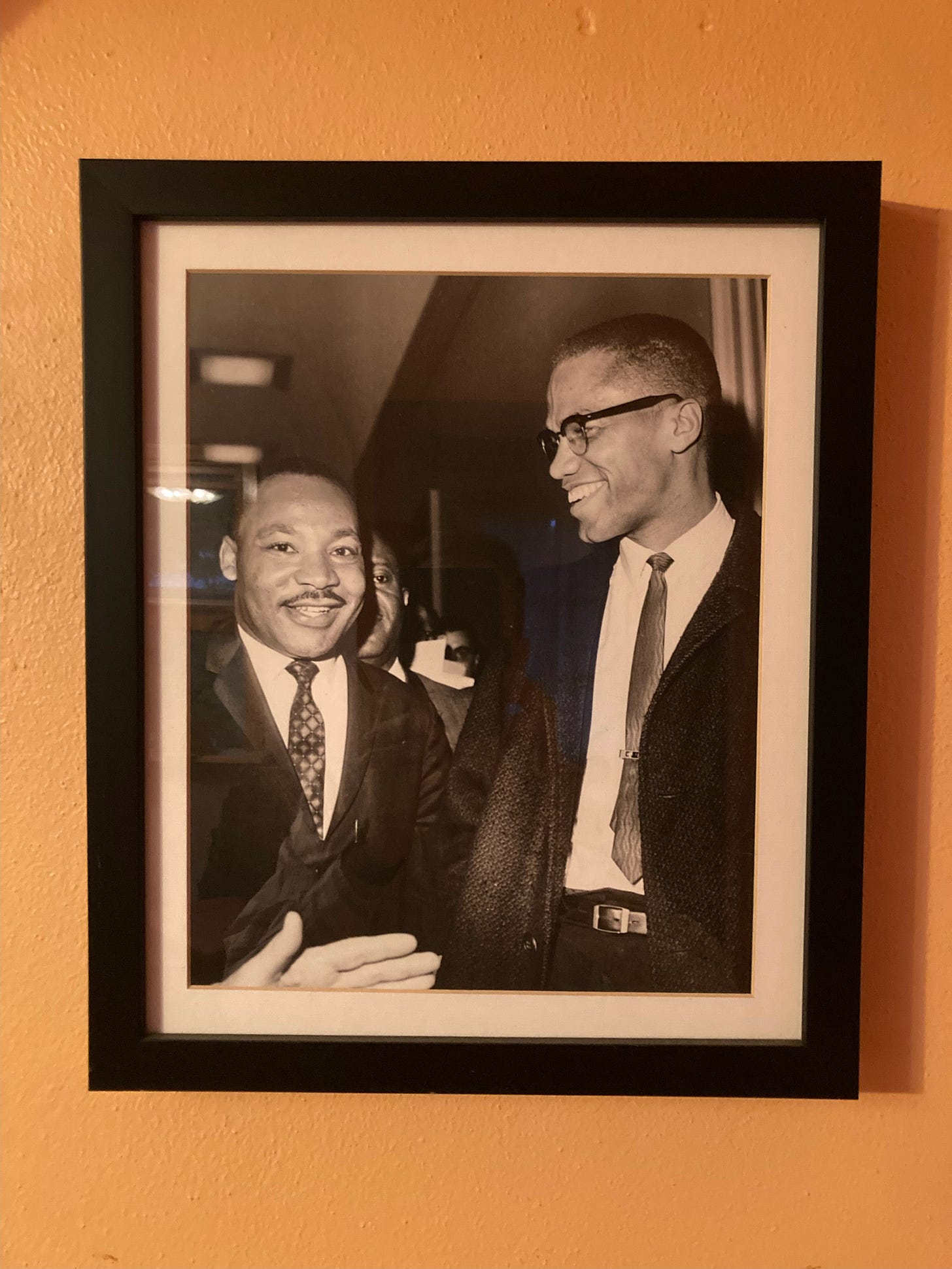

Another thing I think I know, is that what the historians tell us about Dr Martin Luther King and Malcom X is not altogether true, if not a perversion of reality. Towards the end of their lives, their paths and thoughts were converging. They weren’t diametrically opposed, but rather, approaching from two very different life experiences, and came to understand and appreciate each other. This alone tells a different story than what we are told. The photo above hangs in our home to remind us every day of their goodness, their courage, our collective loss, and the need to question The Narrative.

Nina Simone

For half of my career, I worked nights in the hospital. At first it was on a busy medical surgical floor, carrying out the meat and potatoes grunt work of nursing. Then I spent fourteen years working in the Emergency Department, which many laypeople still call the Emergency Room. When the proverbial shit would hit the fan, I would start singing Broadway show tunes. As I was a preceptor for hundreds of students—medical students, paramedic students, nursing students— over the years, I often had the experience that they were surprised and amused at my singing. It was only the people who had worked with me for longer, who understood, eventually. If Scott started singing “Ya Got Trouble” from The Music Man, or “Cell Block Tango” from Chicago, or even more disarming, “The Hills Are Alive” from The Sound of Music, well, you better hold on for dear life.

Long before my singing in the storms of hospitals, because this coping strategy didn’t appear out of nowhere, I was introduced to the music of Nina Simone, and in particular, her song “Mississippi Goddamn.” I was in the back seat of a car, with three other co-counselors, two Black, and another white, returning home from an intense RC weekend workshop about racism. The music was revelatory, profound, and deeply moving. I immediately was drawn to Nina’s juxtaposition of an upbeat show tune’s approach to a deeply disturbing lack of societal response to contemporary racist actions and apathy of the white majority in our country.

This song has been the soundtrack to my life for weeks now. It began when I watched the press conference in which President Trump praised the CEO of Pfizer, and announced that $70 billion of our taxpayer money had been awarded to Pfizer. There stood Secretary Kennedy in the background, who later praised our President. I’m really not taking a potshot at either the President, or Secretary Kennedy. I’m just gobsmacked that given the reality I live as a Covid-shot-injured American, and the long road to recovery for patients I care for in our practice at the Leading Edge Clinic, that anything positive can be said about a murderous CEO and his corporation. Goddamn it, they are still actively trying to kill us with their mRNA shots!

Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” was her explosive reaction to the racist violence tearing through the South in the 1960s—think Medgar Evers’ murder and the Birmingham church bombing that killed four Black girls. But the song isn’t just about those headlines; it’s Simone venting about the whole rotten mess of segregation, violence, and official denial that Black folks were up against. She takes aim at the whole “go slow” attitude—people in power telling the movement to wait, while tragedy piled up.

The name of this tune is Mississippi Goddam

And I mean every word of it

Alabama’s gotten me so upset

Tennessee made me lose my rest

And everybody knows about Mississippi, goddamn

Alabama’s gotten me so upset

Tennessee made me lose my rest

And everybody knows about Mississippi, goddamnCan’t you see it? Can’t you feel it?

It’s all in the air

I can’t stand the pressure much longer

Somebody say a prayerAlabama’s gotten me so upset

Tennessee made me lose my rest

And everybody knows about Mississippi, goddamnThis is a show tune, but the show hasn’t been written for it, yet

Hound dogs on my trail

School children sitting in jail

Black cat cross my path

I think every day’s gonna be my lastLord, have mercy on this land of mine

We all gonna get it in due time

I don’t belong here, I don’t belong there

I’ve even stopped believing in prayerDon’t tell me, I’ll tell you

Me and my people just about due

I’ve been there, so, I know

They keep on saying, “Go slow”But that’s just the trouble (do it slow)

Washing the windows (too slow)

Picking the cotton (too slow)

You’re just plain rotten (too slow)

You’re too damn lazy (too slow)

The thinking is crazy (too slow)

Where am I going? What am I doing?

I don’t know, I don’t knowJust try to do your very best

Stand up, be counted with all the rest

‘Cause everybody knows about Mississippi, goddamnI bet you thought I was kidding, didn’t you?

That raw frustration is what makes Simone’s message still hit hard today. If the system won’t recognize your pain—whether it’s racial violence back then or, for some now, vaccine injury—Simone’s call to shout out, not stay silent, feels just as urgent. The point isn’t to say these struggles are the same, but to notice the pattern: when people get hurt, society is often way too slow to listen or act.

Simone’s anger at being told to “do it slow” is a warning that waiting politely for justice usually means it never comes. And today, anyone who feels dismissed or unheard—by the government, the media, or anyone else—can relate to her demand for recognition and truth. That mix of rage and hope, the refusal to let others decide whose pain matters, is what makes “Mississippi Goddam” a timeless anthem for fighting denial and demanding real change.

Thank you. Powerful writing.

My opinion, you still have remnants of ptsd; and I agree it is good to talk about it (and release some of the tension of the memories). If I had lived your life, I would have a measure of your ptsd also. Sometimes people don't realize that one can have ptsd from "good work" that frequently can cause great anxiety-- sort of like resurrecting anxieties when we were younger and when we did not have even words to apply to what we were experiencing and feeling. My belief, as a generality is that much of ptsd comes from our very young youthfulness when we don't have words to describe our internal emotions and what life is like at those moments. So, we experience relief when the horrid times pass, but those times do not get forgotten and lots of us worry somewhat about "deja vu"--will it come back again, and will we find ourselves just as helpless as when we were kids. I think it does come back, and can come back--it can come back in dementia, in altzheimer's, and pre-death (the last days, weeks, months; and for that reason (I've been with many people in the days/weeks before they died. I recall one old woman who had a black toe that the MD wanted to remove. She refused; and a few months later, her toe healed and regained color. But she also died not long after her toe healed. I visited her once in her living room and saw her turn toward the kitchen entry area and stare. And then I saw her look toward the bedrooms hallway and stare. I asked her what she was looking at. And she said to me, "Don't you see them?" (I didn't see them), but I asked her what do you see? She said, "Angels, they are all over the place. They are in the kitchen and in the hallway." I said, "Isn't that wonderful!" "I guess that means they are introducing themselves to you, and that they are going to hang around waiting for the time to take you to heaven. I think that is as good as it gets. What do you think? She said, Y-E-S. She was happy. She was in peace. It reminds me of my mother in law on the night that she died, about 8 hours after our visit. She saw an "Ark" with a stairway going up into it; and she saw herself standing in front of my wife, hiding my wife behind her, because my wife had a lit cigarette in her hand and she didn't want God to see it, for fear that God would send her back down the stairway into the Ark. That was the first time in 25 years I ever heard my Catholic mother-in-law talk about something spiritual. I was grateful. The next morning she was gone. Those two "old ladies" had, I believe, an important preparation for themselves to die in peace and hope; they were not filled with dread. They had hard lives, but not lives of dread.