Memorial Day of my childhood was mostly uneventful. I was dimly aware of the sacrifices many people in my family and extended community had made to ensure our freedom as American citizens. As a teenager, I would credit my ninth and twelfth-grade social studies teacher, Dr. Roger Breidinger, with opening my eyes to the underbelly of the wars our nation has fought—the pretexts for their initiation and the true reasons behind them. There was the USS Maine, used as a pretext for the Spanish-American War. There was Pearl Harbor at the beginning of World War II, which some historians say was permitted to take place to provide justification for America entering the war. There was the attack on the USS Maddox in the Gulf of Tonkin at the beginning of the Vietnam War.

It isn’t lost on me that Lightning Bug readers are from all over the world, including First Nations people. Many of you live in countries, or countries within countries, e.g. the Crow Nation, which have been pummeled by the United States’ foreign policy and warmaking since before we were a formal country. I’m under no illusion that the freedoms which we possess as Americans have come without harm to other humans in parts of the world distant and near. The home front, the burdens of those who stay behind in wartime, is more universal. Yet there too, I must acknowledge that in modern warfare, the homefront in other countries, especially in developing countries, is often in the combat zone.

When I went to live with my grandparents at the age of fourteen, I met Larry McKenzie and Bonnie Boothroyd, the parents of my new friend Larami. Larry would happily pick me up on Sundays and bring me to Quaker meeting, then drive me home afterward. This was the Quaker version of proselytizing—quietly, gently enabling a young person to be exposed to a paradigm of spiritual and worldly beliefs that could shape his character toward a more peaceful bent.

Living with my Nana and Pop-Pop, I think that I saw an aspect of their relationship that was not as salient for my dad and uncle growing up with them during World War II. My Pop-Pop was twenty four years old in1941. He was the father of two children, and there was no requirement for him to enlist and serve in the war. However, without consulting my Nana, he signed up with the US Marines and then announced this to her after the fact. It was clear to me that she never forgave him for this, and over time, I came to understand some of the intimate details of why.

First, there is the idea that in a marriage, a couple makes decisions together—such as the decision to have children or where to live. In no uncertain manner, my Pop-Pop had completely disregarded my Nana’s thoughts on the subject and took matters out of her hands when he enlisted in the Marines. To hear him tell it, his experience of going into boot camp at Camp Lejeune, traveling to the Pacific, and coming back from the war was an exciting adventure akin to the adult version of Boy Scout camp. My Pop-Pop would retell stories over and over, so I had many opportunities to study his recollections of this time in his life. He would often tell the stories with a light in his eye and a smile on his face, with laughter. He recalled his bridge partner on the troopship who helped him make a fair amount of money. He recalled telling off a general, without the general realizing who he was, and getting away with it. He thought of Camp Lejeune as something that all young men—especially me—should experience in order to straighten them out and teach them how to fly right.

What my Pop-Pop never, ever, ever talked about were the horrors he endured as a US Marine in the Pacific. He served in Okinawa, and most people with even a superficial reading of the history of warfare understand that the campaigns of the US Marines in the Pacific—Okinawa in particular—were akin to meat passing through a grinder. The Japanese had dug in and were fighting to the death. The Marines were burning them out of their caves with flamethrowers. The sight and scent of death were everywhere.

I slept and studied in the bedroom my two uncles had occupied when they were my age. There were two single beds and a little wooden desk in the corner. When I first arrived in Parkerford, there were still some random bits and bobs in the drawers of that desk. Curious boy that I was, I came across a diary of my Pop-Pop’s from when he had first arrived in the Pacific. There were just a couple of entries and then many blank pages. The last entry recounted an attack upon their convoy, which had resulted in many casualties.

The only other war story I ever heard from my Pop-Pop was that of a fellow radar operator with whom he shared a tent. In one of the truly random and horrifying aspects of war, a twin-engine plane flying over Okinawa had been attacked by Japanese fighters, and one of the engines of the plane fell to earth and landed on the person sleeping in the cot next to him in the tent. A shout-out here to anyone who’s ever watched the cult film Donnie Darko. How does a person process such an event, in which their bunkmate is literally squashed into unrecognizable, bloody bits, while you are saved?

But as the title of my Substack portends, this is not meant to be a recounting of the military adventures of the men of the Marsland clan and related step-parents. The people who I never hear celebrated on Memorial Day are the people who stayed behind. I want to write about them and acknowledge their sacrifices, because without them, the soldiers, sailors, and pilots would not have been able to do the dirty work of war.

I’ll start with my Nana. In 1940s terms, my Nana had a nervous breakdown when my Pop-Pop left for the Pacific. She had a newborn and a toddler. A month before, she had not expected or known that my Pop-Pop would be leaving for the other side of the world for an indefinite period of time, with a high likelihood of being killed. They lived in a little town in southeastern Pennsylvania called Spring City. To hear my uncles tell it, it was an idyllic place in which kids had free run of the neighborhood to play pickup baseball and basketball, and all of the yards had victory gardens and fruit trees from which they would freely snack—delicious items such as plums, peaches, pears, and apples. Thankfully, Nana and Pop-Pop had good neighbors, who I never met because they had passed away before I began hearing the stories. They were the Marshalls. If not for the Marshalls, it seems not only possible, but likely that my Nana would have committed suicide. I got to see her depressive episodes 50 years later, and they could leave her in bed for days at a time.

Having just celebrated our 28th year of marital blister and 33 years of cohabitation, I can fully relate to my Pop-Pop’s incredulity that 50 years after the fact, my Nana still couldn’t forgive him for a decision he made long, long ago. The problem is, it was a big fucking decision with a lot of implications.

When I was 18 years old, I spent the summer living in Philadelphia, sharing an apartment with my friend Larami. I worked as a minimum-wage busboy at the Frog Commissary, which was a pretty hot eatery at the time. Larami’s parents had introduced me to a type of peer counseling called Re-evaluation Counseling, and I had taken it to the next level as my own adult person and signed up for a men’s support group which met weekly. That group was a revelation in many ways. It was led by a former IBM computer programmer named Scott Beadenkopf, and it had three gay men in it out of a group of ten. The first support group I went to, I spent most of the time freaking out in my head that there were gay men in the group. I had never met such a real live subject in person, and was terrified that they were going to seduce and molest me. Nothing could’ve been farther from the truth, as I was to learn.

To my even greater astonishment, one of those men had served in the US military. Faggots could serve in the military? I use that pejorative term, which doesn’t cross my lips these days, in order to convey the frame of mind in which I was viewing these other men. What has always moved me in co-counseling is watching what is called a demonstration. Especially when, on the outside, a person looks like they totally have their shit together. It is unsettling to see them, holding hands with another person at the front of the group, avoiding or basking in our attention, depending on their life experience and inclinations, and at some point, potentially breaking down into sobs. I hung on every word of a gay veteran, recalling his induction into the military, his hidden attraction to the men in his unit, the brutality of active combat, and the fact that 40 years later, he was still trying to unpack and process those experiences.

When I was a junior in college, I did something called an externship. This was two weeks of commuting from my Baba’s suburban home in Wyndmoor into Center City Philadelphia, where I volunteered at the ACLU. My mentor for those two weeks was a man named Frank, who was a rare bird—a conscientious objector during World War II. Having lived with my Nana and Pop-Pop and coming to appreciate the enormous peer pressure for a man to join the military during that time, I had some inkling of what huge balls Frank had to have to make that decision. Frank wasn’t even a Mennonite. But what he taught me was that during World War II, he worked alongside Mennonites, who were conscientious objectors inside the mental institutions of the United States. They didn’t just sweep and mop floors. They set to making meaning out of the time they had to serve and can be credited with radically transforming the mental institutions of our country, so that they moved away from the shackle-and-chain approach to one which more fully recognized the humanity of those sentenced as inmates. They helped psychiatrists and civilians start to see those patients as individuals who could be treated.

When I graduated from the Susquehanna University, I really had no idea what I was going to do with my life. Entering into volunteer service was my more peaceful version of the directionless young men and women who entered the military. The Church of the Brethren is one of three denominations in the Protestant camp which has a pacifist tradition, along with the Mennonites and the Quakers. My first assignment was the Catholic Worker House in San Antonio, Texas. Every weekday we ran a soup line, and one of the tasks which fell to the volunteer running the soup line was to ask for a volunteer among the mostly homeless people on the porch if one of them would help with washing dishes. Just like any other arena of life, there are some people who are more active participants and willing to give more of themselves than others. There were two people who consistently volunteered to help. One was a soft-spoken Mexican man who perpetually had his earbuds in and a subtle smile on his face. Another was a tall and disheveled African-American man who still wore an army jacket and had been a veteran—he had served in the Vietnam War.

One of the first things I learned about the homeless population in the United States is that a disproportionate number of them are made up of veterans. If I hadn’t suspected it already, I quickly deduced that all of the rhetoric that public officials bestow upon active military members goes out the window when they return from the theater of war—if they do—with deep emotional trauma. They may feel alienated from their previous life, family, and friends, and seek out the empty solace of alcohol and drugs in order to minimize their daily pain.

When I left the Brethren Volunteer Service, I moved back to Philadelphia. Shortly afterward, I met the woman who would become my wife. Kerrie had two jobs at the time. She worked at a flower market in the Reading Terminal Market full-time, and she had a part-time job in the evenings working at The Ritz, which was an art house cinema in Old City. Endeavoring to woo her, and savoring every moment that we spent together, I would ride my bike across town from my Gray’s Ferry neighborhood to meet her at the end of her shift. The theater manager at the time was a guy named Bill who was a bit of a perv. When he saw me at the door, he would always announce to Kerrie that her love slave had arrived. Because she didn’t have her bike with her, we would typically walk home through one of the four squares surrounding City Hall in Philadelphia, Washington Square.

Washington Square is a peaceful and tree-shaded park. It has a quiet and reflective vibe, and is often less crowded than Logan, Franklin or Rittenhouse Square. It served as a field hospital during the Revolutionary War and is paved with huge flagstones that will shift under your weight. There were some very spooky nights in the winter and the fall that we would be walking through the eerie, lamp-dark of the square, the wind blowing and the leaves rustling, and easily imagine the ghosts of the soldiers and nurses buried under those stones. Depending on the path we chose, we would sometimes walk by the eternal flame of the Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary Soldier. Having traveled the world, I will say that this is one of my favorite monuments because of the meaning of the words written on it.

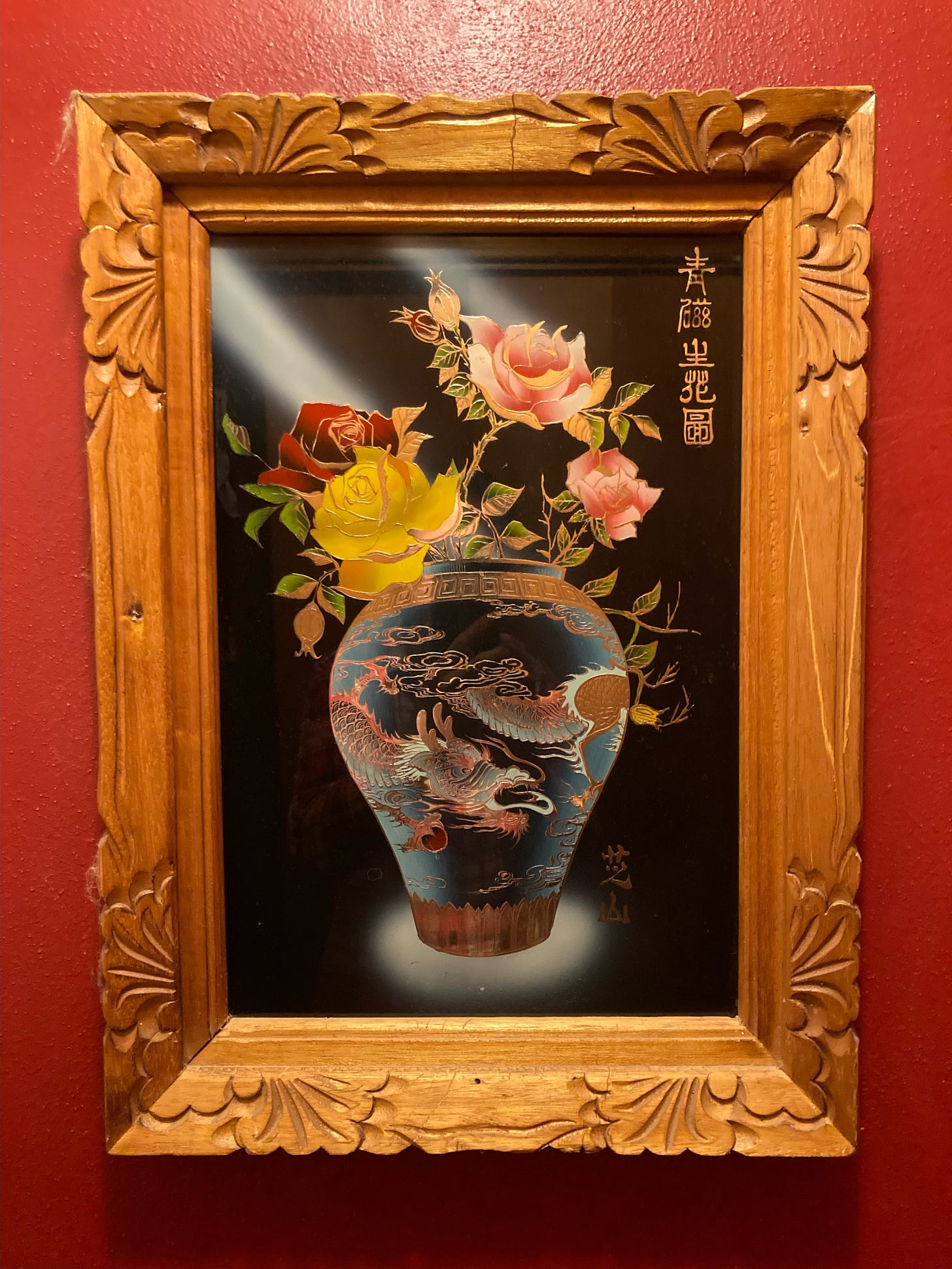

Kerrie’s father served in the Air Force, and for one year during her childhood. He was stationed in South Korea near the DMZ, and Kerrie remained at home with her brother and her mother. That was one of the hardest years of her young life. Her mother suffered from depression and anger, and Kerrie was the focus of many emotional outbursts from her during that time. Her mom began to have an affair with a local police officer who would come over in the evenings and leave in the mornings. As a girl, she knew that that wasn’t right, but certainly couldn’t speak up against it. When her dad returned from Korea, he brought a gift to Kerrie, which was a reverse glass painting, which was very popular in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Chinese characters on the painting suggest good fortune and prosperity. I think of Curt, and that time in Kerrie’s life, every time I’m in the foyer of our home where that artwork still hangs.

On this Memorial Day, I give thanks to the men and women who served in the military of our country throughout history, their tremendous sacrifices, and I pray for the healing of those living and those who have passed. Today, on this Memorial Day, I give even greater thanks to those that kept the home fires burning. To my Nana, to the Marshalls, to Frank, to the children who missed their parents, to the children who lost their parents—your sacrifices have not gone unnoticed.

Beautiful and moving piece. Thank you, Scott—and beautiful work, Kerrie.

Kerrie's work continues to be so beautiful. Thanks for your compassionate essay and for sharing her talent.