The Hippocampus Under Siege (Part 5)

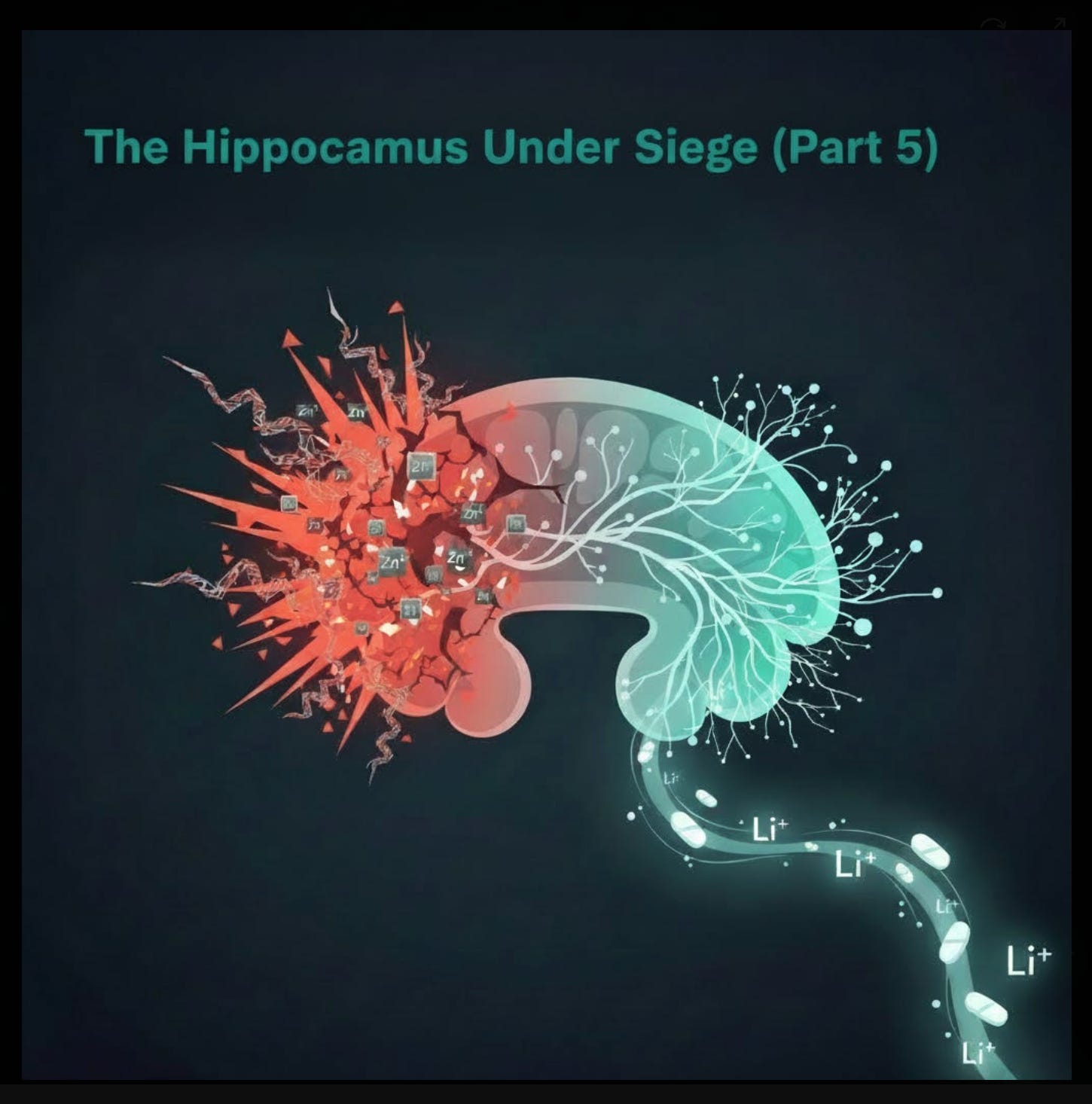

Spike protein, zinc excess, and the erosion of nemory, motivation, and identity — why low-dose lithium orotate has become a cornerstone in our PASC and vaccine-Injury treatment

The Brain Region Where Joie de Vivre Lives

By mid-2024, a quiet pattern had emerged in our clinic. Patients who had recovered much of their physical stamina still described something deeper and more disturbing: a loss of who they used to be. They spoke of flattened motivation (“I don’t care about anything anymore”), dulled emotional range (“I can’t feel joy or even sadness properly”), and fragmented long-term memory (“I know things happened, but I can’t feel the timeline”). They were still curious, and questioned things, because these were Leading Edge Clinic patients after all. But, these weren’t just complaints of brain fog or fatigue; they felt like assaults on identity itself.

The common thread pointed to one structure: the hippocampus. The hippocampus is not just a memory center; it is the adult brain’s primary site of neurogenesis—the birth of new neurons from neural stem cells in the dentate gyrus. It is essential for contextual memory, emotional regulation, and the flexible thinking that underlies motivation and a sense of self.

When explaining the potential memory changes to patients, I would say, “With dementia, you may not remember that you had turkey for dinner last night. With harm to the hippocampus, you may not remember that Thanksgiving when your dog stole the turkey from the kitchen counter while no one was looking. And when your family is recounting this event from collective experience and laughing during a holiday dinner, you are mystified.” For those who are old enough to know what cassette tapes are, I would say, “It’s like running out of storage space to write new memories; someone recorded traffic noise over your most favorite Paul Simon album, Graceland.”

When neurogenesis slows or stops, the brain loses its ability to update its internal map of reality. Old patterns harden; new learning becomes difficult; motivation fades because the future feels indistinguishable from the past. Some patients described exactly that: a world that had become gray, predictable, and strangely small. The question became: what was attacking the hippocampus so consistently in this population?

The March 2024 Meeting That Was “Life-Changing”

A turning point came in March 2024, when my partner Dr. Pierre Kory, our colleague Dr. Paul Marik, and I sat down for a Zoom call with the German scientist and author Dr. Michael Nehls. What was supposed to be a routine scientific discussion turned into one of the life-changing conversations which seem to be happening more and more since the pandemic. Nehls laid out his thesis from The Indoctrinated Brain (2023): SARS-CoV-2 spike protein acts as a direct neurotoxin capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, triggering chronic microglial activation, cytokine release, and suppression of adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus.

He connected the dots between hippocampal atrophy and the exact constellation of symptoms we were seeing—loss of autobiographical depth, flattened affect, reduced motivation, and a pervasive sense that “I’m not me anymore.” That call sent us down a new path. We began exploring low-dose lithium orotate as a targeted intervention to stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis and restore BDNF signaling. It was a trace mineral, missing from the diets of most people, and cost pennies. Horbaach made a version which cost $15.00 for a six month supply (including shipping), now, suspiciously, out of production. Within weeks of reading Nehls and implementing the protocol, we saw the first signs that this approach could meaningfully reverse some of the damage.

Spike Protein and the Hippocampal Assault

Nehls’ framework is supported by converging preclinical and clinical evidence. Spike protein (from infection or mRNA vaccine-encoded S-protein) binds ACE2, neuropilin-1, and TLR4 on brain endothelial cells, disrupting tight junctions and increasing BBB permeability. Once inside the parenchyma, spike activates microglia and astrocytes, releasing IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and other pro-inflammatory mediators that inhibit neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation in the dentate gyrus. Human autopsy and imaging data from severe COVID-19 cases reveal hippocampal atrophy, reduced dentate gyrus volume, and elevated markers of neuroinflammation. Longitudinal studies of milder PASC patients show persistent reductions in hippocampal function, correlating with memory complaints and motivational deficits.

Nehls argues this erosion is not incidental but functionally significant: reduced neurogenesis impairs the brain’s ability to generate new autobiographical narratives, question authority, or imagine alternative futures—leaving individuals more compliant and less resilient. Put your arms straight out in front of you, walk stiffly, and repeat after me: “Safe and effective, safe and effective, safe and effective.” Whether or not one accepts the sociopolitical framing, the biological claim is increasingly difficult to dismiss: spike protein exposure appears to preferentially damage the hippocampus, eroding exactly the capacities (memory, motivation, identity, joie de vivre) that patients describe losing.

Zinc Excess and the Second Hit Hypothesis

This is where zinc re-enters the picture. The hippocampus has the highest concentration of zinc in the brain—~200–300 μM in synaptic vesicles, released during long-term potentiation (LTP) to modulate synaptic strength and memory consolidation. Zinc is essential here: it stabilizes NMDA receptor function, supports BDNF/TrkB signaling, and promotes neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus.

But excess zinc flips the switch from protective to destructive. Chronic high intake disrupts zinc homeostasis (via impaired ZnT-3 vesicular transport), leading to paradoxical local zinc deficiency in the hippocampus despite systemic excess. Rodent studies show high-zinc diets cause hippocampal atrophy, reduced BDNF expression, impaired spatial memory, and depression-like behaviors—symptoms that mirror PASC complaints. Excess zinc also triggers excitotoxicity through AMPA/kainate receptor potentiation and intracellular zinc overload, producing ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptotic cascades in CA3 and dentate gyrus neurons.

In a healthy brain, these effects might be buffered. But in a hippocampus already under siege from spike protein–induced inflammation, BBB leakiness, and suppressed neurogenesis, even moderate zinc excess could become the second hit that tips the system into irreversible decline. The rapid cognitive and emotional improvements we’ve seen after tapering zinc—even in patients taking balanced zinc-copper formulas—suggest that this vulnerability is clinically relevant.

Low-Dose Lithium Orotate: A Cornerstone for Hippocampal Recovery

Faced with this double assault (spike + excess zinc), we needed a countermeasure that could directly stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis, restore BDNF signaling, and dampen neuroinflammation without adding new risks. Following the March 2024 call with Nehls, low-dose lithium orotate (1 mg elemental lithium for maintenance, 5 mg for symptomatic patients) became that tool—and quickly a cornerstone of our protocol. Mind you, this was before we learned about low-dose sublingual ketamine the following year. See Part 6 of this series for that piece of the puzzle.

Lithium has one of the strongest evidence bases for promoting adult hippocampal neurogenesis. It inhibits GSK-3β, upregulates BDNF and Bcl-2, reduces microglial activation, and protects against excitotoxicity and tau phosphorylation. In rodent models of chronic stress, inflammation, and neurodegeneration, low-dose lithium increases dentate gyrus progenitor proliferation, improves pattern separation, and reverses depression-like behaviors. Human studies (mostly low-dose carbonate or orotate) show similar effects: increased hippocampal volume on MRI, improved memory performance, and enhanced emotional resilience in mood disorders.

Orotate is particularly attractive because it crosses the BBB more efficiently than carbonate at much lower doses, minimizing risk of thyroid or renal toxicity while retaining neurotrophic benefits. In our practice, we have observed consistent improvements in motivation, emotional range, autobiographical recall, and critical thinking after adding lithium orotate—often within 4–8 weeks. Patients describe “feeling like myself again,” or “the colors came back.” These are not universal, but they are frequent enough—and often profound enough—to make lithium a non-negotiable part of our approach for patients with prominent hippocampal symptoms.

Importantly, lithium orotate appears to buffer zinc-related injury as well. It chelates excess metals, stabilizes zinc transporters (ZnT-3), and protects against zinc-induced excitotoxicity in preclinical models. In a population already vulnerable to mineral imbalance, this dual action—stimulating repair while mitigating further damage—makes low-dose lithium orotate a rational, evidence-informed addition.

References for Part 5

Krasemann S, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein alters barrier function in 2D static and 3D microfluidic in-vitro models of the human blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;146:105131. DOI: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105131

Song E, et al. Neuroinvasion of SARS-CoV-2 in human and mouse brain. J Exp Med. 2021;218(3):e20202135. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20202135

Meinhardt J, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(2):168–175. DOI: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5

De Felice FG, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces neuroinflammatory response in brain endothelial cells. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):185. DOI: 10.1186/s12974-021-02227-3

Thakur KT, et al. COVID-19 neuropathology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York Presbyterian Hospital. Brain. 2021;144(9):2696–2708. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awab148

Lu Y, et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in long COVID: A preliminary MRI study. J Neurol Sci. 2023;448:120619. DOI: 10.1016/j.jns.2023.120619

Douaud G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022;604(7907):697–707. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5

Sensi SL, et al. Zinc in the physiology and pathology of the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(11):780–791. DOI: 10.1038/nrn2734

Adamo AM, et al. Zinc overload in the hippocampus impairs memory and BDNF signaling. J Neurochem. 2019;149(5):618–632. DOI: 10.1111/jnc.14714

Yang Y, et al. Excess zinc impairs hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function in rats. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1230–1245. DOI: 10.3390/nu5041230

Morris DR, Levenson CW. Zinc in the developing brain. Adv Neurobiol. 2017;18:87–110. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-55769-4_3

Sensi SL, et al. Zinc in excitotoxicity. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21(10):395–401. DOI: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01563-3

Weiss JH, et al. Zinc and excitotoxicity. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21(10):395–401. DOI: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01563-3

Chen RW, et al. Lithium protects against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2003;84(4):746–754. DOI: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01576.x

Son H, et al. Lithium enhances adult hippocampal neurogenesis via GSK-3β inhibition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(10):1955–1964. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2013.96

Silva R, et al. Lithium increases hippocampal neurogenesis in stressed rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(4):299–307. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.09.004

O’Leary OF, et al. Lithium-induced increase in neurogenesis is associated with antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(3):657–666. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2011.226

Moore GJ, et al. Lithium increases N-acetyl-aspartate in the human brain. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(1):1–5. DOI: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00868-1

Yucel K, et al. Lithium-induced increases in hippocampal and thalamic gray matter volumes in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(4):381–386. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.022

Sartori SB, et al. Lithium orotate is superior to lithium carbonate in crossing the blood-brain barrier. J Neural Transm. 2016;123(12):1405–1413. DOI: 10.1007/s00702-016-1575-9

Chen RW, et al. Lithium attenuates zinc-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2003;84(4):746–754. DOI: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01576.x

Kim YH, et al. Lithium modulates zinc transporter expression in neuronal cells. Neurochem Int. 2011;59(5):678–684. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.06.010

Scott, between you and Pierre it is almost impossible to keep up with your writing (just got my copies of War on Chlorine Dioxide). What you are doing is amazing, the patient care, research and writing about it. When I was a kid in the 60s and 70s we had some genuine hero's in the US. It's been a long time but we again have true hero's now. Thank you!

Hi, where can we find the other parts of the hippocampus series? I don’t see them on the Substack page. Thanks so much.